GaymerX was a great time - it was great to see a lot of friendly faces, and i was really proud of

Toni Rocca and co. for organizing a fan conference specifically catered towards making a safe space for LGBTQ gamers, a thing the industry normally gives next to no shits about. the video of my talk should be going online in the future. in the meantime, though, enjoy the text.

also if you like my work,

support me on Patreon! as part of my Patreon i have an exciting music-related development planned in the next month that should be forthcoming, so stay tuned. thank you all so much!

This is from an

excellent article by James Bridle from the Guardian last week:

The first electronic general-purpose computer, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer), was built at the University of Pennsylvania between 1941 and 1946. It was designed to calculate the range of heavy artillery for the US army. The size of a couple of rooms, it had thousands of components and millions of hand-soldered connections. The computer scientist Harry Reed, who worked on it, recalled that the ENIAC was "strangely, a very personal computer. Now we think of a personal computer as one which you carry around with you. The ENIAC was actually one that you kind of lived inside. So instead of you holding a computer, the computer held you.

Reed's observation is more apt, and more persistent, than he lets on. The computers haven't really got smaller; they've got much, much larger, from the satellite relays we consult every time we get GPS directions to the vast server farms in windowless sheds on ring roads which we have chosen to call "the cloud". That this computation is less visible than it was in Reed's day, when an observer could follow the progress of a calculation in blinking lights across the room, doesn't make it less pervasive. The digital is both the infrastructure and the mode of our daily communication, and shapes our culture at every level. In the majority of the developed world, it is the foundation on which our personal lives are built, and multinational corporations operate; it underpins global communications and global wars. It is, in essence, in everything.

Given this, it seems crucial that it is also accessible to all; not merely engineers, scientists, politicians and policy-makers, but also artists, commentators and the general public. There has never been a greater need for critical engagement with the role technology plays in society, but there's a corresponding problem with that engagement, as severe now as it was when CP Snow diagnosed it in 1959: the lack of understanding between the sciences and the humanities.

If anything, digital technologies have rendered this problem even more acute, as the vast and smoking industrial architectures of the 20th century give way to the invisible, intangible digital architectures of the 21st. If technological literacy is going to rise, it's going to need the help of artists to enlarge its vocabulary, and the leadership and guidance of cultural institutions to frame the discussion.

i know this is a videogame conference, but i really wanna stress that this talk is not just about videogames. this is about the way that we interact with the world, through these digital architectures. this is about finding ways to use and reclaim expressive tools to empower ourselves, and to speak out against injustices in the world, and to escape oppressive ideology. this is about being scientists as well as artists. this is about human struggles of the 21st century, and games are sitting in the middle of it all.

so where do we start?

i'm choosing to do this talk at a fan conference, and not at an industry, or a professional, or an academic one, because I think there are serious issues of accessibility in game spaces - both in the past and in the present. it's there in what is and isn't talked about, and who was there to see it, and who was speaking. and i'm not just talking about mainstream 'gamer; culture spaces, but also indie game culture and academia that studies videogames, and digital art spaces, even in queer and marginalized game spaces. there's not only issues of racism and sexism and transphobia and homophobia and ableism, but things like classism and regionalism that play in who is there to enjoy and experience what, and who it speaks to.

that's not to say that there isn't a lot of progress being made towards inclusivity in a very short period of time, and a lot of voices are at least given some support and allowed to speak openly when they weren't before - queer people, trans people, people of color, women. and we have some events like this one here springing up, that focus on particular marginalized groups or ideas.

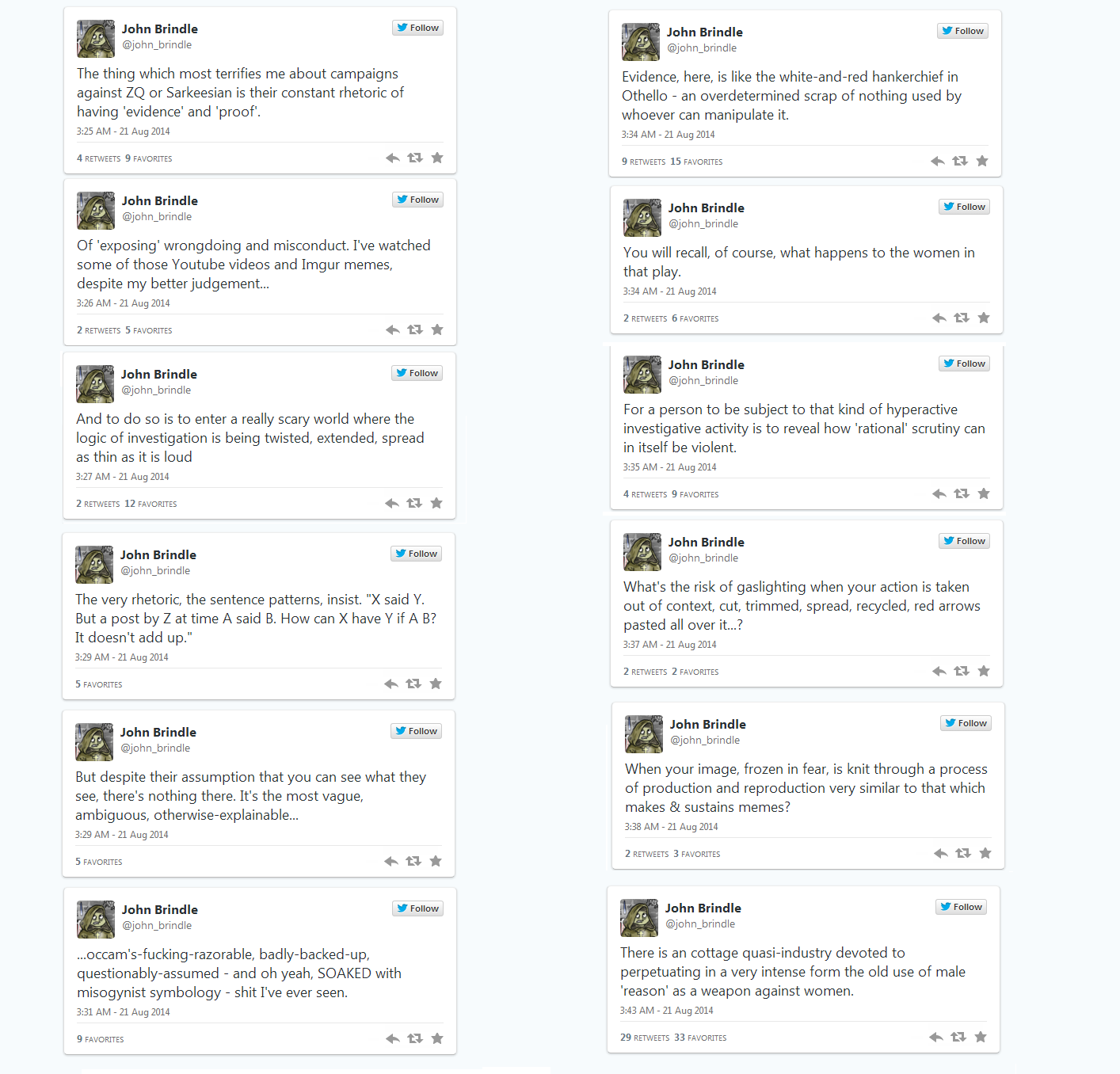

but these voices speaking at these conferences also are speaking to a much smaller number of people, because they're not given the kind of mouthpieces that industry figures are. or when they are, the few who are, they face an immense amount of harassment, and put themselves in great personal danger every time they speak up. it's not a safe place to be. and because of that, these worlds outside the mainstream - indie games, queer games, etc. can seem insular and overly inward-directed to outsiders - or more like social groups than movements. it can seem like knowledge of them is used as a currency, or like they're "pretentious", or like everyone is giving themselves a pat on the back for making a cool new thing. a lot of games are made, a lot things are written about, and without relevant signposts it's hard to tell who is aligned with whom, who is talking to whom, and where this is all going.

i will say right now in these progressive game spaces there seems to be a spirit of collective exhaustion. events like Independent Games Festival have more-or-less fully calcified into a groups of haves and have-nots, with the vast majority of recognition and financial success still being dominated by white males. this is especially, by the way, true in areas of expertise not immediately related to "gender equality" or activism - if you look at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at GDC from this past year, for example, there was 1 woman on a panel of over 20 speakers. even those very the small number of games that do aim towards a mass-market receive immense amounts of backlash from gamers who charge them with ruining videogames with their social justice activism. for an example, check out

many of the Steam reviews for Gone Home.

it's true that more women and queer people and people of color are being invited to conferences - but they often don't have the positions of financial security to where they can afford to actually speak at them, especially because a lot of conferences won't pay their speakers air fare or lodging costs. Mattie Brice, for example,

wrote this year about how she spoke at 14 different conferences but was still struggling to make any kind of living because of taking out loans for school and living in SF. we think of someone with that level of ubiquity as having "made it", right? but the usual providers of that security - the game industry, and the games press, - salary jobs with benefits, essentially - have continually shown a lack of commitment to promoting actual equality or job security in their fields, and a lack of interest in hiring people that may in any way actively challenge the status quo.

this is from an industry survey, originally from Game Developer Magazine, featured in

an article on the game industry last year in Jacobin, which i will quote from heavily later:

The job with the most female representation, producer, clocked in at just 23 percent and an average salary $7,000 less than males’. Female programmers stand at 4 percent; QA, the front door to a career in the industry, at a woeful 7 percent.

the games press is currently undergoing the same issues.

a month or so ago the site Giant Bomb announced they were hiring. there were several visible female journalists that seemed very qualified and likely to join a crew that's historically been guys - including people like Cara Ellison, Mattie Brice, Kris Ligman, Maddy Myers, but they chose to go with another guy - Dan Ryckert from Game Informer. this ended up igniting an already running controversy on the twitterverse about how marginalized game writers - ones, especially, who are putting a lot of effort into listening and writing about less-covered voices and games - can't seem to find sustainable salaries, but are expected to keep working while struggling to make any kind of living off what they're doing.

this is a quote from

a post by Samantha Allen on tumblr:

I have to ask myself every time I write a piece if I’m emotionally prepared for the comments and if that toll is worth a freelancer’s pay. My orbit might be more stable but I’m still one comments section away from giving up. One day, I’ll ask myself that question, “Is it worth it?” and the answer will be “No.”

Patreons—imperfect stopgaps that they are—keep popping up while the jobs keep going to the boys. There’s only so many times we can hear “next time” before we know they’re lying.

Something’s changing in us, I think. We’re through living in between “next times.” Those of us, like me, who have financial support elsewhere and are doing this out of passion are starting to wonder whether our passion is misplaced or, worse, dangerous. Those of us who have tried to secure support within the system are realizing we probably won’t find it.

but this problem is not just a matter affecting marginalized writers. the structure of the industry actively inhibits this kind of growth from happening in the larger culture, both in the ethical problems with the way the game industry operates and the way it uses the signposts of a shared geek culture to manipulate people's desires.

from

the aforementioned article on Jacobin, which is called "You can Sleep Here All Night"

There’s a dearth of rigorous coverage of the industry. The video game press, such as it is, remains mired in a culture of payola and ad revenue addiction, outside of a few outlets. The one television station devoted to industry news, G4 (which has moved away from covering only video games), seemed committed to proving every gamer stereotype true, with an endless parade of uncritical corporate press releases punctuated only by sophomoric oral sex jokes.

All of which is a shame, because something in the industry is wrong. Here, as in few other places, we see the kind of exploitation normally associated with the industrial sector in creative work. Already subject to lower wages when compared to the broader tech sector, video game studios’ management maintain the status quo by consciously manipulating the desires of writers, artists, and coders hoping to break into a creative field. The profit vacuumed up goes to ever more bloated management salaries and the unremittingly glitzy, tacky spectacles churned out by gaming’s PR departments.

The exploitation in the video game industry provides a glimpse at how the rest of us may be working in years to come.

he goes onto talk about his coworkers past experiences when he joined the industry as a QA Engineer at Funcom in 2007:

Most of my coworkers viewed their gigs at Funcom as having “arrived.” Almost all of them had come through Red Storm, one of the most respected studios in the country and an industry linchpin in North Carolina. The stories they told were galling: gross underpayment, severe overworking, and middle management treating the cubicle farm as a little fiefdom all their own.

Red Storm at the time employed the bulk of their QAs as temps. Lured in by promises of working their way up the ladder, scores of college kids and young workers would come in, ready to make it in the new Hollywood of the video game industry. The pay was minimum wage. The hours were long, with one of my immediate supervisors casually stating that he regularly worked at least 60 hours a week during his time there. Being temps, there were no benefits.

This would go on for the duration of a project, usually the final four months or so. When the temps weren’t needed anymore, it was common for groups of them to be rounded up, summarily let go without notice, and told that a call would be forthcoming if their services were needed again."

this, by the way, is a common scenario on the industry. there's an article on Kotaku recently that covers a lot of the recent big layoffs in the industry and how its affected employees. i recommend checking out. anyway:

"There were other stories – strange and mean ones, like the producer who waltzed into the QA office and asked if anyone was heading for the dumpster. When no one answered, she dropped a big bag of garbage in the middle of the floor, snarled, “I guess I’ll just leave this here, then,” and stalked off; the QA lead chewed them out since the woman was a producer, a project manager.

Everyone who came through related the same story of QA’s complete sequestration from the development team; nobody was allowed to speak to a “dev” directly, only through intermediaries, nor to enter the dev side of the building. The QA temps were a clear underclass on one floor, while full-time “real” video game workers occupied the other.

At the time, I didn’t understand why someone wouldn’t leave such a situation. The pay was awful, the hours too long, and it sounded like a rotten place to work if even a fraction of the stories I’d hear over lunch breaks were true.

But everyone kept returning to some variation of the same theme: it was their dream to work in the video game industry.

you might not be so surprised to find out that this sentiment is echoed throughout the industry:

paraphrased from the article: in a 2008 panel at the International Game Developers Association, while serving on the board, then president of Epic Games Mike Capps...

...stated bluntly that Epic would not hire people willing to work for less than 60 hours a week; that this was not a quality of life issue but a matter of Epic’s corporate culture, and that it was patently absurd that anyone getting into the industry shouldn't expect the same.

this caused a firestorm at the time, but then when you look in the much more recent industry figures reported by Game Developer Magazine:

A whopping 84 percent of respondents work “crunch time,” those notorious 41+ hour work weeks which line up with the end of big projects. Of those, 32 percent worked 61-80 hours week (and usually goes on for months).

indie games also are not much of a viable alternative to many:

Indie games, the only currently viable ticket to breaking the stranglehold of the big studios, are a ticket to poverty. The average indie worker made $23,000 a year.

the article talks about how these things are commonly justified because through the idea of passion, and having passion for games

Again and again, when you read interviews or watch industry trade shows like E3, “passion” is used as a word to describe the ideal employee. Translated, “passion” means someone willing to buy into the dream of becoming a video game developer so much that sane hours and adequate compensation are willingly turned away. Constant harping on video game workers’ passion becomes the means by which management implicitly justifies extreme worker abuse.

And it works because that sense of passion is very real. The first time that you walk through the door at an industry job, you’re taken with it. You enter knowing that every single person in the building shares a common interest with you and an appreciation for the art of crafting a game. Friendships can be built immediately – to this day, many of my best friends arose from that immediate commonality we all had on the job.

...

Geek culture takes such strongly held commonalities of interest and consumption far more seriously than most other subcultures. I recently wrote a piece for this publication which was, in part, about the replacement of traditional class, gender, and racial solidarity with a culture of consumption. Here, in the video game creation business, is the way capital harnesses geek culture to actively harm workers. The exchange is simple: you will work 60-hour weeks for a quarter less than other software fields; in exchange, you have a seat at the table of your primary identifying culture’s ruling class.

this 'passion' is not only used to justify industry abuse towards workers and general bad industry practices, but it's used to create and maintain an idea of a culture that benefits those in power. it's used to exclude minorities and women. it's used to define the lines of people's behavior, and their preferences, and how they see and construct themselves and their identities. videogame culture is an extension of this larger fan or geek culture, most of which comes from large media empires that come from large fictional fantasy universes like Star Wars or D&D - their vagueness and openness lets their fans project themselves onto the world pretty much in any way they can imagine. and these worlds can be really powerful and useful imaginative outlets to lots of people. but the really insidious thing is that they're so much at the control of corporate entity to change and exploit the means with which they can do that at a moment's notice.

Katherine Cross yesterday was talking about she essentially transitioned through WoW - that it was one of the few outlets that let her express her identity. but when Blizzard decided to make take away the anonymity it made that no longer possible for others to do that and be stealth. the control of one of the few places that allowed the safe expression of queer or alternate identities was now eliminated. out of a supposed effort to clean up the community make people more accountable online abuse, they erased an entire population who was using it for refuge.

to go back to "passion" and videogames - the first time i saw Mario 3, when i was 3, it seemed so real and tangible. yet there was something unreachable about it - and videogames in general. it was a luxury object for the richer kids. my parents would never buy me current generation systems, so i had to desire them from afar. and that felt really shitty. i felt like i was missing out. they felt like this real culture i wasn't experiencing in the isolated place i grew up in. full of fun and colorful worlds constantly played up by advertising on all the cartoons i'd watch. desires were, more and more, being implanted into me as a vulnerable child by the world around me. and they were desires defined by genuine creative impulses, but they were being exploited.

i felt owed videogames - because they felt so real, because they felt like they'd compensate for other bad things in my life. they were taking part in that shared culture i never got to experience otherwise. years later i'd tried to collect old games, and download a bunch of rom-sets and enjoy what i wasn't able to in the past, but the feeling was never the same. the idealized image i had of them was gone.

at a certain point down the pipeline, the desire that was created in me by the culture around me became way more about preying on my emotional insecurities than about any inherent, genuine creative spark or passion. i felt entitled to more, but after awhile everything seemed boring - not immediate enough. not cool enough. the desires created a deep, untenable sense of entitlement. an entitlement that we see manifesting itself all over videogame culture in many different forms. it's one that the companies that helped tremendously to foster it into existence are having an increasingly difficult time maintaining with any degree of stability.

the fact is, videogame companies - and Nintendo in particular, took advantage of the fact that they were using an exciting new technology, the genuine creative impulse that exists people have to explore outside their world (in a culture that can be pretty oppressive as far as creative outlets are concerned), and the youngness and impressionability of its target demographic, to create this sense of entitlement.

and then, when you try to challenge them. when you try to interrogate them, you find out that they don't actually give you a way into them. a game like Mario 3 may let you look at it from 100 different angles, when most games will only let you look at them from a few, but it will still never let you inside. it will never let you look into the machine and break apart the game into its component parts. it's tremendously enjoyable. it's an alluring and complex object, much moreso than other games, but it's still a closed one. and that's no secret. it's how it's designed - it's a product. it's a toy.

companies like Nintendo and Apple are very good at marketing towards the technical anxieties of their users. they make closed boxes, and they make those closed boxes tremendously sexy. they make them into a larger idea, a lifestyle. they make it fun, and they make it a toy, or a fashion accessory - but you have to actively subvert the will of the company to actually get inside it.

-------------------

contrary to Nintendo and console games, i have more lasting memories about the PC games i'd play when i was young. these are the ones that, at the time, i felt like i was stuck with, and that it was hard to find people who'd heard of. the weird knock-offs of more successful titles. Commander Keen and Jill of the Jungle and shareware games. that world, if only because it was less ubiquitous in culture, ended up becoming my world, and the one i come back to much more often.

the PC has a long history of being a subversive box. when i saw Doom, in particular, for the first time on a friend's computer, it felt like something incredibly new - not just in the violence and in the game's darkness, but in the depth. it was upsetting and scary for someone my age - but i had a traumatic childhood, and this felt more real than anything else. it wasn't just about "fun" or challenge - they were trying to get inside your head. but it was not only this, but in the fact that there was an active modding community. the fact that you could play multiplayer. you could play it different ways. they willingly opened up the box and let you change things around inside. they encouraged it. and maybe it took away from some of the enclosedness of it, but in exchange you got an active community of creators and modders doing whatever they wanted with it.

as it turns out, Doom's spirit of letting the user in didn't originate with id software, or DOS. the 80's was a boom for personal computers like the Commodore 64 or ZX Spectrum or Apple II. while none of them had the mass appeal of the NES, they featured tools that let you program your own games. magazines would print out code you could compile to your own program. it gave you a power - one that was limited to people who could afford it, of course, but one that was there. it was from this that the developers of Doom, and many of the people who changed the industry, came from. maybe those C64 or ZX Spectrum games weren't so smooth or as complete a package as Mario, they were looser, much different - and as such maybe more exciting when you look back at them.

that's not to say that a lot of these games didn't have serious problems. or that there hasn't been a huge strain of libertarian white dudes ideology dominating the spaces around these games. but our gaze is different in 2014 than it was in the 80's - and looking those older games can help us escape from the, quite frankly, suffocating ideology behind what is a "game" and what isn't that we're stuck with in the present.

On

Summer Games Done Quick - a speedrunning stream, the speedrunner Cosmo did a run of ZZT a game by Tim Sweeny from 1991 (the founder of Epic Games). on the couch, one of the other runners and volunteers at the event spent the entire run laughing at the game's ANSI art style and saying stuff like "is this even real?" and "did you make this up?" and "this is not even a videogame". no one on the stream really seemed to bat an eye. in 1991, ZZT was most definitely a game. in 2014, it's no longer a game. sorry. these games existed in smaller worlds, where a pretty big breadth of things things co-existed, and where people didn't really care too much if there were other people who wanted to do something different from them.

i think we've let the winners write the history for us, and use its machinery to devalue and erase most of the threads of the past. which is why we need to pay extra close attention to the past, and use what we can from anything we can find to our advantage. we can use that genuine passion from playing a Nintendo game as a kid to our advantage too, instead of just using as a way to conform in the same ways to what is essentially corporate ideology. we can look deep at the design of it and what makes it tick - and interrogate it, and challenge it, and appropriate it, and apply it to a more free and open space.

even something like modding an old game can be a revolutionary act in today's culture depending on how we use it. for those of you who follow me on twitter - i've mentioned this many times, but there's a Doom mod named

A.L.T. that i'm particularly fond of because of the way it uses a very unconventional and challenging style of design to tell a story. the story, in itself, isn't anything too amazing, but playing through is levels almost has the feeling of experiencing a manifesto for what can even be achieved in a simple framework like Doom's gameplay. there's a sense urgency to it. it both speaks to the experience of playing a game like Doom and something much deeper and more intangiable. its instability and restlessness is exciting.

i feel that same sense of urgency when i look at some more recent demoscene art. particularly of

PWP, also known as viznut, who has written on his website about aiming to use demoscene art - which has been traditionally a way of showing off technical prowess - to make social or cultural statements. in a video like

this one you see old videogame styles and iconography gleefully co-opted to make an anti-authoritarian message. it's powerful and its direct, but it doesn't come off as pretentious. it's something more strange and intangiable. and exciting.

that sense of urgency is also something i see when i look back at some old net art from the 90's like is mentioned in the

Guardian article i quoted from at the beginning..

My Boyfriend Came Back From The War by Olia Lialina was a piece of art in 1996 that pretty much in every way resembles a Twine game from authors you see today.

or there's

http://wwwwwwwww.jodi.org/, not assigned a specific name beyond the strange URL and serious of cryptic symbols and navigation on the pages. but then, if you use the browser's option to view the source code, you see what sits behind the system - a detailed schematic of a nuclear bomb. the idea of this very sinister undercurrent hidden behind the seemingly unparseable surface presentation that defines our way of life, of sinister oppression beneath layers of obscurity and legalese. that there is an immediate and obvious truth, but it is hidden in the intentionally obfuscating nuts and bolts of the system.

these are art of their time, defined by the technology of their time, in the particular scenes of their time - and you know, fine art spaces do have a way of keeping a lot of people outside those worlds from getting into them. but also much more prescient and ageless, and speak a lot more to videogames than most "gamey" games do. they are oddly also seem to be more relevant now than they were at the time.

that sense of urgency, that kind of aggressive adventurousness, that willingness to use any means possible to break out escape oppressive ideology needs to permeate into our art and into our games now. the fact is, the lines have been drawn. digital architectures run the world now. stuff like social media is a game, and one that, built into deep into their structure, is being played against us. and if we hope to change the way the game is played, we have to look straight into the machine and make sense of how it works, and use whatever tools at our disposal. we need to think very very consciously be thinking about the means we make it in, how we disseminate it. how we advertise it. or what tools we use. because those are the kind of things that have a deep, and powerful effect on other people - and ultimately what will hollow out these oppressive ideologies that have held such a strong grip on people's consciousness - and make the world a more empowered, more compassionate, more exciting, and more livable place.