this is level six from the shareware episode of a videogame released in 1993 by Apogee Software for the Disk Operating System (aka DOS). the most notable thing about this game, beyond that it's a lesser-known predecessor to the game that turned the pop-trash-culture-quipping icon of hyper-misogyny Duke Nukem into a household name, is that it's in many ways a pretty egregious rip-off of the Turrican series, particularly Turrican 2, and borrows many game ideas (and graphics) from it. i could go into great detail on the extent of the things that are ripped off from that series, some rather pointlessly or randomly, but that isn't really the point. the point, for me, is that i played Duke Nukem 2 when i was young and impressionable, and hadn't even heard of Turrican 2 until maybe last year.

because of the highly-embraced ugly values of what the Duke Nukem of Duke 3D and beyond represents in the "gaming pantheon", it would be easy for anyone who identifies as any kind of self-respecting feminist to mercilessly trash these games. not to mention that i have a friend in the industry who sees Apogee/3D Realms's business guy Scott Miller as an piece of utter human garbage because of the way he conducted his company over the years. but as is the case with many commercial games over the medium's history, the DN games tell contradicting stories.

these kind of games always led a very transient existence. the crushing wave of constant technological advancement that forced developers to constantly make their games bigger, longer, faster, better-looking or be left in the dust ensured this. in a year or two (maybe less), they'd become completely irrelevant, and players would seek out something else. the point was to just make whatever you thought might make money within the narrow gap of time you had that hopefully aligned with your own interests as a designer. most of the design decisions made in that era end up being attributed to the consumer demand (or at least perceived consumer demand) or not having enough time to think of anything better, or just plain ignorance. designers still didn't really know what they were doing at all, but had at least a decade of experiments and mistakes behind them to build off of. the more perceptive and imaginative designers seemed to have some kind of intuitive sense that there was a vocabulary of design decisions that were maybe "cool" and ones that were "uncool", and how to be interesting and engaging while still making something that could sell, even if they didn't know how to articulate this consciously. or maybe, in the end, it was mostly just luck and being in the right place at the right time while being too dumb to know any better.

games and anything game-like were, meanwhile, very deeply marginalized by larger culture. the media acted as if games couldn't be anything but these quirky, abstract little kid's toys. by the end of the 90's, developers were starting to undertake greater efforts to make games more "real" so they could be some kind of participant in mainstream (usually film) culture. this is where you began to see a split between games packaging themselves on the surface as purporting to be some part of larger, more "legitimate" cultural tradition, and the still very "videogamey" design decisions made by many designers. over the years, a couple of different narratives have floated around, both of which marginalize the "videogamey" side. people in the industry now tend to see that kind of abstraction as a relic of technological limitations or designer ignorance that games had to accept because they didn't have the processing power to make more realistic human environments. the educated, culturally-aware people who wish for games to become something "greater" now have mostly learned to accept that games must completely wear on their surface their hope to be a part of larger culture. anything that might seemingly run counter to that must be falsely empowering, "videogamey" nonsense.

what popular culture remembers about Duke Nukem 3D is that in the first level you could go into a movie theater and watch an animation of a scantily clad woman and you could blow a hole in the woman to find a secret, and in a later level there was a strip club and you could play pool and pay the strippers to strip or kill them. anyone playing the game now might be very confused to find that the experience of actually playing the game is much weirder and more unsettling than they probably ever remembered. one might forget that there was a second episode (my favorite) entirely set in space with all kinds of

evocative,

abstract, and

terrifying environments. Ken Silverman's Build engine led to an explosion of creativity for the level designers, who were presumably looking to take complexity of environments one step further from previous FPS games like Doom. but the winners write the history on their own terms. the Bruce Campbell wannabe character Duke Nukem quickly wrote over anything in the game of his namesake that might contradict what he stood for.

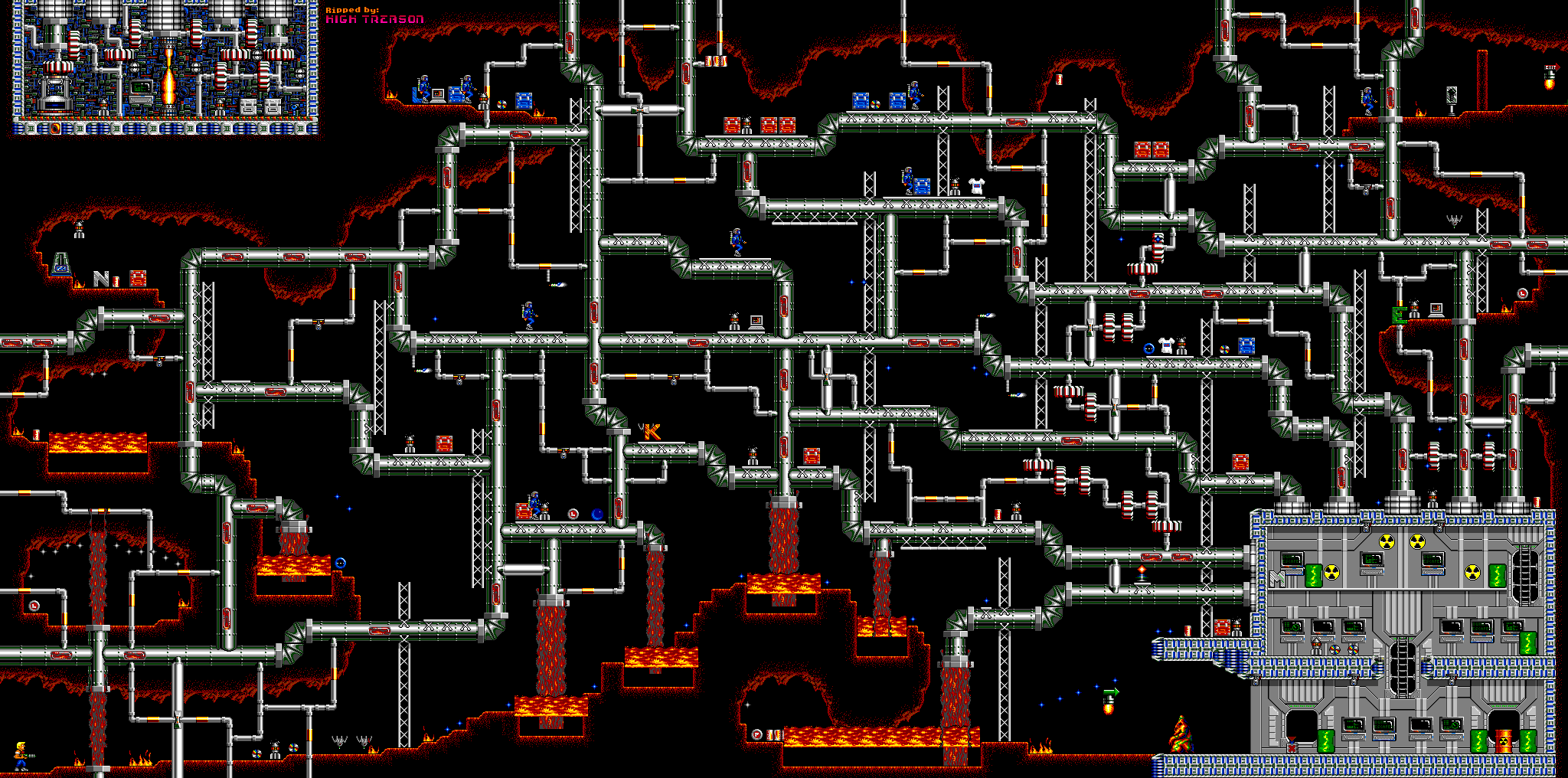

in the case of level six of Duke Nukem 2, pictured above, there is so much fucking

weird shit cluttering up the environment. you wander around climbing ladders and jumping from pipe to pipe, killing guards and disabling robot drones and shooting open differently colored boxes that will give you more health or weapon power or points and searching for where to go. as it turns out, you don't need any items to reach the teleporter that leads you to the key you need, in the area on the bottom right of the map where the pipes connect up to (though powerups help). there is a stronger, mini-boss style flame enemy, a save point, and bunch of guards on computer terminals who are guarding a teleport to go inside the machinery to the area on the top left of the screen, where the key is. once you have the key, you can use it to open the exit on the top right of the level.

this all seems easy enough, but because the size of your screen is so small, the act of navigation is very confusing (

you can see this in this video playthrough of the level). it's really hard to tell where you need to be at any given time. it seems as if the pipes could just go on in every direction, forever, and there are so many fucking boxes hiding items around, some helpful, some that hurt you to add to the confusion. and yet, there's a beauty to the level that can only be witnessed when it's completely zoomed out like in the image above. piece by piece, through playing the level, you build some kind of relationship with it and begin to construct an image of a coherently functioning environment in your head that might look something like what we can see in the image above, though you'll never actually see that image in the game.

this clever level design, by far one of the most well-realized in the game, seems like it's really undermined by requiring players to be engaged with so much cluttering, seemingly pointless shit from moment-to-moment to get from point A to point B. that stuff was probably all in there because the developers thought it was cool to add more features, not because there's a particularly conscious story the item boxes or turret-bots are trying to tell. young and impressionable me might not have understood why the boxes are there, but accepted them as part of the game and built my own interpretation of the narrative around them. the feeling of playing Duke Nukem 2 was about being overwhelmed and confused by these frustratingly abstract, winding, futuristic hellscapes. it was a game about the world's intense over-saturation of technology turning it into a kind of terrifying wasteland, yet there was something still oddly exciting about it all.

compare this to, let's say, level 8-1 of the first Super Mario Bros game (right click and "open in new tab" to make it bigger).

in a typical 2D Mario game, most levels look like some kind of long horizontal strip. the design is intentionally directing the player towards making a series of linear, moment-to-moment decisions. there's next to no backtracking, or maze navigation, or confusion. in Mario you do have a coins and points and power-ups, and 8-1 is a frustrating trap of a level in many ways: but the game always, no matter what, makes you feel like you know exactly what you need to do and that the end is always within your grasp.

we tend to view that as "good design" and the swirling, incomprehensible mess of a game like Duke Nukem 2 as "bad design". Mario 1 understands what its function is, Duke Nukem 2 doesn't. i won't say that this isn't correct on one level, but it still completely misses the point.

so Duke Nukem games seemed to have no real idea of what that were about, beyond things stolen from other games, until they decided to be about a misogynist bully - and by then it was far too late to erase all of the counter-threads that had been running through those games up to that point. and thank fucking god for that, really. the first game (which i have a special relationship with and hope to write about more), was a clunky, puzzle-filled techno-futurist platformer. the second tried to be less incomprehensible and clunky and move towards a faster action game, but ended up at some awkward point in between the first and some kind of grotesque Turrican rip-off. both are alienating, sometimes weirdly intense experiences to play now.

Duke Nukem 3D was a point of high absurdity for games, built with a bunch of hyper-complex, interactive, abstract environments of keys and switches in the vein of Doom (though often more obviously representational of "real" environments), all masked by the idiotic ugliness of its newly culturally aware protagonist. the marketing story told by the Scott Millers of the industry overwrote the design story told by the Todd Replogles or Allen Blums or Ken Silvermans. afterwards, nothing like it could ever hope to exist. no self-respecting game designer afterwards could ever purport, without extreme embarrassment, to make one kind of game and actually make a completely different one. no self-respecting game designer could ever hope to get away with creating a character as stupid as Duke Nukem ever again, either. the game was an unstable beast that pulled itself apart and pissed on anything that might have hoped to come after.

and so videogames "grew up", but instead of learning to love and embrace their own unique, sometimes seemingly incomprehensible and "videogamey" design vocabulary, they opted instead to convince themselves that they were moving forward, torching the confusing design threads and cognitive dissonances of the past in an endless, stupid search for cultural acceptance. people wanted "real" environments, and "real" stories that they could connect with, so that's what they got. a game like Duke Nukem 2 is now an embarrassment and a relic because it couldn't understand what it was about. a game like Duke 3D is only remembered for its pathetic stabs at cultural legitimacy, and all the idiocy that came after.

i see many game designers of 2013 engaging in a peculiar kind of self-flagellation. they want to erase all the embarrassment of the Duke Nukem 3Ds of the past, instead of trying to come up with any understanding of why games like that existed or what relevant counter-threads the games themselves might offer now. in a post Duke 3D world, they can no longer recall that anything other than the narrative they now accept about videogames ever existed, or if they do they see the past as immature and messy and not at all useful or relevant for the future. they're videogame monks who are trying to retain some idea of purity by completely cleansing themselves of all their previous sins. they're vast oceans away from accepting that the greatest insight tends to be found in the messiest, stupidest, and most broken of places. they stood aside and let the Scott Millers of the world write the story.

if videogames can't love themselves, why should i love them?